Dr. Beckwith, who was formerly president of the Evangelical Theological Society recently converted or reverted to the Catholic Church of his youth.

An interesting read if you'd like to understand the reasons for his conversion out of the Church and his reasons for returning.

He Could No Longer Explain Why He Wasn’t Catholic

Until a few weeks ago, Francis Beckwith was president of the Evangelical Theological Society, an association of 4,300 Protestant theologians. Now he has returned to the Church of his baptism.

BY Tim Drake

June 3-9, 2007 Issue | Posted 5/29/07 at 8:00 AM

Until a few weeks ago, Francis Beckwith served as president of the Evangelical Theological Society, an association of 4,300 Protestant theologians.

That was until he made the announcement on the Right Reason blog of his return to the Catholic faith of his youth. Beckwith returned to the Church after 32 years as an evangelical. The online “storm” that followed led Beckwith to resign as president of the prestigious society.

He serves as associate professor of church-state studies at Baylor University. He spoke recently to Register senior writer Tim Drake from his home in Waco, Texas.

It’s been a while now since your announcement. Can you believe your reversion is still generating so much online discussion?

No, it’s beyond remarkable. Prior to my announcement, our blog averaged 1,500 hits per day. The weekend after my announcement, it hit 20,000. We’re still getting between 5,000 and 7,000 per day.

You were born into a Catholic family. When did you leave the Catholic Church?

I was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1960. My mother, Elizabeth, also born in Brooklyn, is Italian-American. My father, Harold Beckwith, was born in Connecticut. I’m the eldest of their four children. In the mid-1960s we moved to Las Vegas, Nev., where my father worked as an accountant and internal auditor at a number of hotels. In the late 1970s, both he and mother founded Sweets of Las Vegas, a candy business that had two retail stores in the area.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was part of the first generation of Catholics who would have no memory of the Church prior to Vatican II. This also meant that I grew up, and attended Catholic schools, during a time in which well-meaning Catholic leaders were testing all sorts of innovations in the Church, many of which were deleterious to the proper formation of young people.

On the other hand, there were some very important renewal movements in the Church at the time.

The Catholic Charismatic Movement had a profound impact on me.

During my middle school years, while attending Maranatha House, a Jesus People church in downtown Vegas, I also frequented a Catholic Charismatic Bible study. Some of the folks at that Bible study were instrumental in bringing to my parents’ parish three Dominican priests who offered a week-long evening seminar on the Bible and the Christian life. I attended that seminar and was very much taken by the Dominicans’ erudition and deep spirituality, and the love of Jesus that was evident in the way they conducted themselves.

But I was also impressed with the personal warmth and commitment to Scripture that I found among charismatic Protestants with whom I had interacted at Maranatha House.

Looking back, and knowing what I know now, I believe that the Church’s weakness was presenting the renewal movements as something new and not part of the Church’s theological traditions.

For someone like me, who was interested in both the spiritual and intellectual grounding of the Christian faith, I didn’t need the “folk Mass” with cute nuns and hip priests playing “Kumbaya” with guitars, tambourines and harmonicas. And it was all badly done.

After all, we listened to the Byrds, Neil Young and Bob Dylan, and we knew the Church just couldn’t compete with them.

But that’s what the Church offered to the young people of my day: lousy pop music and a gutted Mass. If they were trying to make Catholicism unattractive to young and inquisitive Catholics, they were succeeding.

What I needed, and what many of us desired, were intelligent and winsome ambassadors for Christ who knew the intellectual basis for the Catholic faith, respected and understood the solemnity and theological truths behind the liturgy, and could explain the renewal movements in light of these.

You spent 32 years in the evangelical world. What could Catholics learn from evangelicals?

I learned plenty, and for that reason I do not believe I ceased to be an evangelical when I returned to the Church. What I ceased to be was a Protestant. For I believe, as Pope Benedict has preached, that the Church itself needs to nurture within it an evangelical spirit. There are, as we know, too many Catholics whose faith needs to be renewed and emboldened.

There is much that I learned as a Protestant evangelical that has left an indelible mark on me and formed the person I am today. For that reason, it accompanies me back to the Church.

For instance, because Protestant evangelicals accept much of the Great Tradition that Catholics take for granted — such as the Catholic creeds and the inspiration of Scripture — but without recourse to the Church’s authority, they have produced important and significant works in systematic theology and philosophical theology.

Catholics would do well to plumb these works, since in them Protestant evangelicals often provide the biblical and philosophical scaffolding that influenced the Church Fathers that developed the catholic creeds as well as the Church’s understanding of the Bible as God’s Word.

But these evangelicals do so by using contemporary language and addressing contemporary concerns. This will help Catholics understand the reasoning behind the classical doctrines.

In terms of expository preaching, as well as teaching the laity, Protestant evangelicals are without peers in the Christian world.

For instance, it is not unusual for evangelical churches to host major conferences on theological issues in which leading scholars address lay audiences in order to equip them to share their faith with their neighbors, friends, etc. Works by evangelical philosophers and theologians such as [J.P.] Moreland, [Paul] Copan, and William Lane Craig, should be in the library of any serious Catholic who wants to be equipped to respond to contemporary challenges to the Christian faith.

Have you been surprised by the hostility of some of the reactions to your reversion?

Some of the hostility was not surprising, for some of it came from well-meaning Protestants who simply do not have a good grounding in Christian history or the Catholic Catechism. Many of these well-meaning folks, unfortunately, have sat under the teachings of less-than-careful Bible-church preachers and pastors who approach Catholicism with a cluster of flawed categories that make even a charitable reading of the Catechism almost impossible.

I actually think there are different circles of evangelicals that overlap each other. There are those who interact with Catholics, and those who don’t. I have been with the group that has interacted for quite a while because of my discipline of philosophy and because the cultural issues that I write on are the ones around which evangelicals and Catholics have been aligned.

I knew there were differences and that they were important ones, and that there would be those who would not be entirely happy with my becoming Catholic, but I didn’t think there would be those who thought I was becoming apostate as some of my commentators have indicated online.

The “First Things” evangelicals — those who interact with Catholics — don’t think that serious Catholics are not Christians. Even in their own denominations, there are those who are not serious believers. Because I ran in these overlapping circles, I underestimated people who didn’t do that. There are people who just attended ETS meetings and did their own education and teaching in evangelical schools. In a way, I underestimated that there was that much distance between evangelicals and Catholics in certain enclaves.

What led you back to the Church?

There isn’t just one reason. One reason alone isn’t enough. That’s like someone asking, “Why do you love your wife?” There are 15 different reasons. It’s the whole package.

My nephew asking me to be his sponsor for his May 13 confirmation merely sped up what I had intended to do in November after my term as ETS president had ended.

I didn’t fully realize it until the beginning of 2007 that I had assimilated much of a Catholic understanding of faith and reason, the nature of the human person, as well as the progress of dogma.

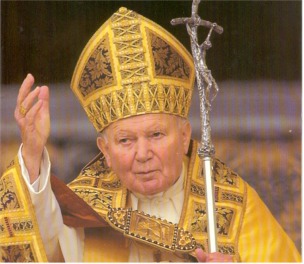

Looking back, the beginning of my return to the Church, though I didn’t realize it at the time, probably occurred at a conference on John Paul II and Philosophy at Boston College in February 2006.

Several months earlier I had published a small essay in the magazine Touchstone: “Vatican Bible School: What John Paul II Can Teach Evangelicals.” I incorporated portions of that essay in my BC paper in which I made a case for why anti-creedal Protestants hold to an incoherent point of view on faith, reason, and the nature of the Christian university.

The first question from the audience came from Laura Garcia, a BC philosophy professor, who is a Catholic and former evangelical Protestant.

She asked, “Why aren’t you a Catholic?”

The question took me by surprise.

I gave her an answer — if I remember correctly — that appealed to the doctrines of the Reformation as making all the difference to me. I also tried to account for the church’s continuity as being connected to the reformers and their progeny as well as their predecessors in the Catholic Church. In this way, I could defend the creeds as Spirit-directed without conceding the present authority of Rome on these matters.

That episode at Boston College, nevertheless, got me thinking.

So, I read Truth and Tolerance by Ratzinger and portions of his Introduction to Christianity. Out of curiosity, I picked up a book I saw while browsing the stacks at a local bookstore: David Currie, Born Fundamentalist, Born-Again Catholic.

I was not entirely convinced by all his arguments, but he did raise some issues about the Church Fathers and the Catholic doctrines of the Eucharist and infant baptism that led me to more scholarly sources.

In mid-November I was elected president of ETS while still embracing Reformation theology on the four key issues I just mentioned.

In early January 2007, I began reading the Early Church Fathers and the Catechism, focusing on the doctrines that I thought were key.

I also read Mark Noll’s book, Is the Reformation Over?

This led me to read the “Joint Declaration on Justification” by Lutheran and Catholic scholars. While consulting these sources, I read portions of a book by my friends Norm Geisler and Ralph MacKenzie, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals: Agreements and Differences. It is a fair-minded book.

But some of the points that Norm and Ralph made really shook me up and were instrumental in facilitating my return to the Church.

What was their take on the issue you had just read about, justification?

For example, in their section on salvation, they write: “Although the forensic aspect of justification stressed by Reformation theology is scarcely found prior to the Reformation, there is continuity between medieval Catholicism and the Reformers” (103).

Then when I read the Fathers, those closest to the Apostles, the Reformation doctrine was just not there.

To be sure, salvation by grace was there. To be sure, the necessity of faith was there. And to be sure, our works apart from God’s grace was decried. But what was present was a profound understanding of how saving faith was not a singular event that took place “on a Wednesday,” to quote a famous Gospel song, but that it was the grace of God working through me as I acquiesced to God’s spirit to allow his grace to shape and mold my character so that I may be conformed to the image of Christ. I also found it in the Catechism.

There was an aesthetic aspect to this well: The Catholic view of justification elegantly tied together James and Paul and the teachings of Jesus that put a premium on a believer’s faithful practice of Christian charity.

Catholicism does not teach “works righteousness.” It teaches faith in action as a manifestation of God’s grace in one’s life. That’s why Abraham’s faith results in righteousness only when he attempts to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice to God.

Then I read the Council of Trent, which some Protestant friends had suggested I do. What I found was shocking. I found a document that had been nearly universally misrepresented by many Protestants, including some friends.

I do not believe, however, that the misrepresentation is the result of purposeful deception. But rather, it is the result of reading Trent with Protestant assumptions and without a charitable disposition.

For example, Trent talks about the four causes of justification, which correspond somewhat to Aristotle’s four causes. None of these causes is the work of the individual Christian. For, according to Trent, God’s grace does all the work. However, Trent does condemn “faith alone,” but what it means is mere intellectual assent without allowing God’s grace to be manifested in one’s actions and communion with the Church. This is why Trent also condemns justification by works.

I am convinced that the typical “Council of Trent” rant found on anti-Catholic websites is the Protestant equivalent of the secular urban legend that everyone prior to Columbus believed in a flat earth.

You dug even further back than Trent, though.

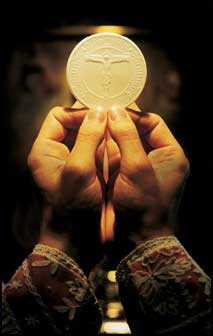

I returned again to the Fathers and found in them, very early on, [confirming] the Real Presence, infant baptism and apostolic succession, as well as other “Catholic” doctrines.

Even in the cases where these doctrines were not articulated in their contemporary formulations, their primitive versions were surely there.

But what was shocking to me is that one never finds in the Fathers’ claims that these doctrines are “unbiblical” or “apostate” or “not Christian,” as one finds in contemporary anti-Catholic fundamentalist literature. So, at worst, I thought, the Catholic doctrines were considered legitimate options early on in Church history by the men who were discipled by the apostles and/or the apostles’ disciples.

At best, the Catholic doctrines are part of the deposit of faith passed on to the successors of the apostles and preserved by the teaching authority of the Catholic Church.

At this point, I thought, if I reject the Catholic Church, there is good reason for one to believe I am rejecting the Church that Christ himself established.

That’s not a risk I was willing to take.

After all, if I return to the Church and participate in the sacraments, I lose nothing, since I would still be a follower of Jesus and believe everything that the catholic creeds teach, as I have always believed. But if the Church is right about itself and the sacraments, I acquire graces I would have not otherwise received.

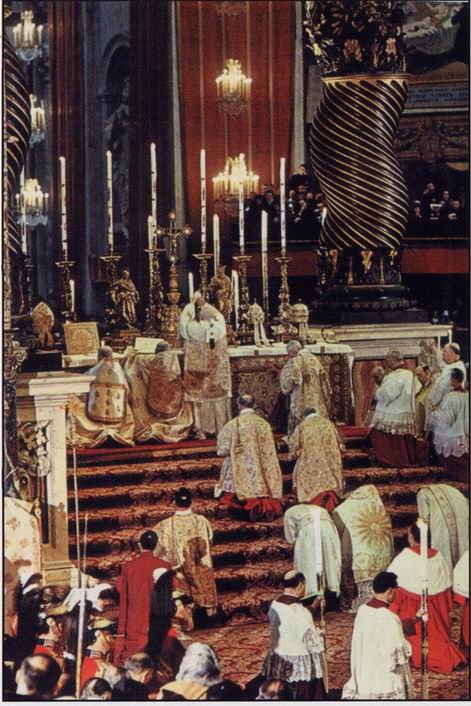

So, on March 23, 2007, my wife and I met with a local priest and told him of our intent to seek full communion with the Church. We decided that I would go through RCIA with my wife and that we would both be received into the Church at the end of my ETS presidency in November.

A week later, I attended a special executive meeting of the ETS in Fort Worth. I was torn up about telling my friends on the committee. But since the meeting was for the exclusive purpose of charting for the future the group’s administrative structure, I knew that if I told my colleagues of what I had planned to do in November after my presidency that we would never address the important business at hand.

So, the meeting went as planned.

However, after that meeting, I sought counsel with numerous friends, both Protestants and Catholics, about what I should do about my ETS presidency and membership. I shared those deliberations on a May 5 entry on the blog to which I contribute, “Right Reason.”

Some commentators have raised questions about your faith in the Church’s authority. How would you respond?

I accept the Catechism. I wouldn’t have become Catholic if I didn’t. Obviously, because the Church has a teaching authority that doesn’t mean that there aren’t issues on which you can debate and discuss.

I do think that one of the difficulties that some Protestants have is that they have an authoritarian model of Catholicism — that there are guys sitting in Rome making these things up — and that’s unfair to Catholicism.

Because of the magisterium, contemporary leaders, in some ways, are constrained by the precedents of the past. That is more sure of a foundation than one would find in the evangelical world, where a congregation can vote, by fiat, things in or out. I accept the authority of the Church for very good reasons, just as I would accept what my doctor says because he went to medical school.

What can evangelicals and Catholics learn from one another?

As I have already noted, I believe that Catholics can learn from evangelical Protestants how to preach, teach and offer support for doctrines and beliefs that Catholics often just leave to authority.

Evangelicals can learn from Catholics that Christianity is a historical faith that did not vanish from the earth between the second and 16th centuries. That is what I mean by “learning from the Great Tradition.”

Much of what evangelicals think of as the odd beliefs of Catholics have their roots deep in Christian history. This, of course, may not convince a Protestant that these views are correct. But what it will do is help the Protestant to appreciate that the very same Christians that deliberated over the content of the Biblical canon also believed in the Real Presence, purgatory, intercession of the saints and indulgences.

If these Christians, who knew the Bible far better than us, did not think these practices and beliefs “unbiblical,” one should not be so quick to dismiss these practices and beliefs simply because they are outside of one’s Protestant experience.

On the other hand, the fact that many Catholic parishes do not offer the expository preaching and theological teaching to their members found in the best Protestant churches should force Catholics to critically reflect on whether they are adequately evangelizing and equipping their own people to enter a world hostile to the Christian worldview.

We have much to learn from each other.

Tim Drake is based in

St. Joseph, Minnesota.

![[Unam Sanctam]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiymQ2adTjpZ1ABhPBbBBquiPCxeQrc4Jy_97vOikT0wGQeJleriiXQy6ebnb0jrYe-TfvcK77txStB4aIwVAdD41ZdMkVfNtFGC0JX6LBV9B8mfeRZaIAM7Sj-011ag3DiKQzv/s1600/headerdivinemercy.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment