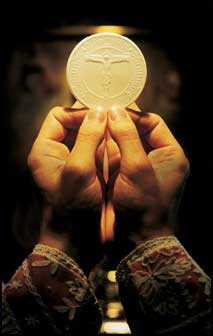

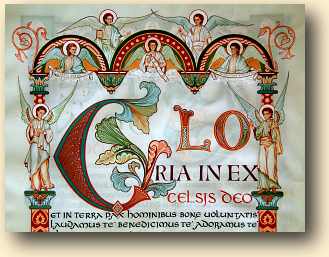

Yup. That's right. I kid you not. All that glorious art on the altar pieces that you thought were painted on canvas? They're actually mosaic copies, tesserae, painstakingly pieced together by the master mosaicists. Except the 17th century painting of the Holy Trinity, by Pietro da Cortona above the altar in the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, all of the paintings have been replaced with mosaics - and you'd never be able to tell they're not paintings unless you looked very closely - so they're very durable and photography is allowed inside the church without damaging the priceless works of art.

Take the Altar of the Lie below for example. Verily, cant's thou tell that it is indeed not a painting? I prithee, take a closer look.

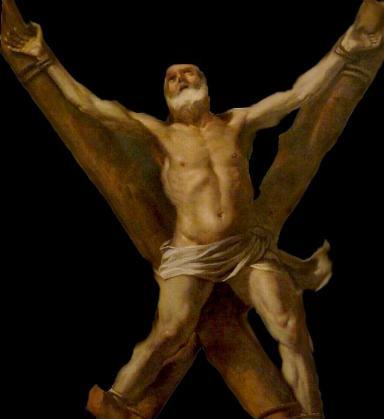

The Altar of the Lie, a strange name for an altar; it refers to a story from the Acts of the Apostles, depicted in the mosaic. The first Christians shared all their property, and none of the claimed private ownership of any possessions (Acts 4:32). A couple that had converted, named Ananias and Sapphira, agreed to sell their property and give everything to the Christian community. But they kept part of the proceeds. St Peter reproached Ananias for telling a lie to the Holy Spirit. Ananias fell down dead. His wife came about three hours later, and she, too, lied about the money. Peter asked her why she wished to test the Spirit of the Lord, and said that the men who had carried her husband's body out would carry her too, at which she dropped dead at his feet. (Acts, 5, 1-10). In the background, you can see a depiction of the men carrying Ananias' body out for burial.

The Altar of the Lie, a strange name for an altar; it refers to a story from the Acts of the Apostles, depicted in the mosaic. The first Christians shared all their property, and none of the claimed private ownership of any possessions (Acts 4:32). A couple that had converted, named Ananias and Sapphira, agreed to sell their property and give everything to the Christian community. But they kept part of the proceeds. St Peter reproached Ananias for telling a lie to the Holy Spirit. Ananias fell down dead. His wife came about three hours later, and she, too, lied about the money. Peter asked her why she wished to test the Spirit of the Lord, and said that the men who had carried her husband's body out would carry her too, at which she dropped dead at his feet. (Acts, 5, 1-10). In the background, you can see a depiction of the men carrying Ananias' body out for burial.

Look closer and you can see the details of the mosaic. The photo below shows the individual tesserae that comprise the mosaic. The Vatican Mosaic Studio has apparently developed 15,000 different shades of colour.

|

|

|

| Priceless paintings that grace the altars of the Vatican Basilica are recreated in mosaic glass by master mosaicists. Details from the Annunziata |

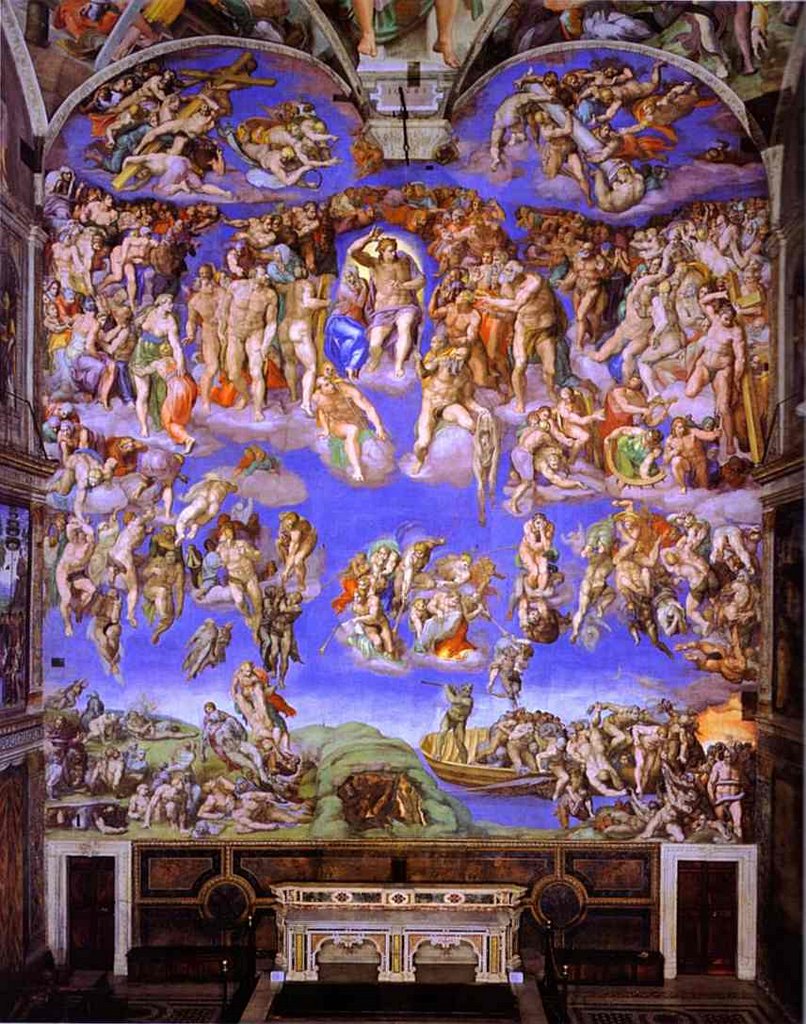

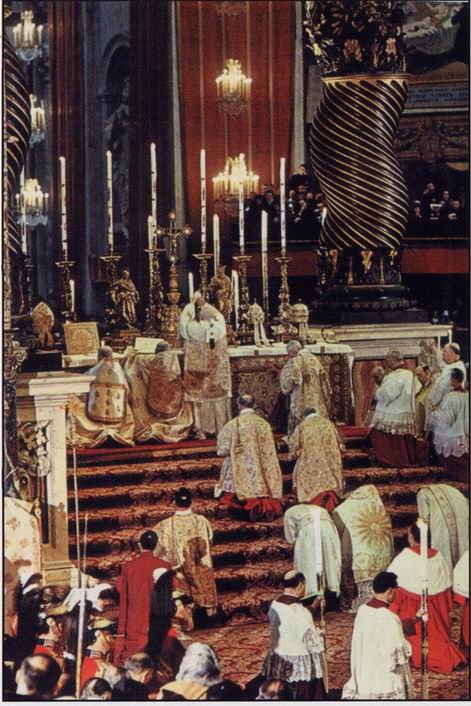

Toward the end of the 16th century, the construction of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome was drawing to an end. Rising above the sepulcher of the Apostle Peter, the composition of decorative works designed by Michelangelo and Bramante had begun on the magnificent wall structures of the central cruciform dome. During those years, Palaeo-Christian walls and floors were usually covered with mosaic works. The ancient basilica's facade and wooden frameworks were usually gilded with mosaics, running the length of the portico and narrating to pilgrims the stories of the apostles Peter and Paul.

The decorations of the new basilica began with the vault of the Gregorian chapel in 1578 and were executed by the Venetian mosaicist Marcello Provenzale. Provenzale was summoned from Venice, where the art had been handed down for centuries within the basilica of San Marco. Shortly after, a school was formed under the title of Fabbrica di San Pietro. Here, under the guidance of the Venetian masters, an increasing number of Roman artisans learned the art of mosaic and then applied these skills to the incredible works of St. Peter's.

Initially, mosaics were used on the vaults of vestibules and chapels, while altarpieces were painted on canvas. But these proved to be easily perishable due to the basilica's unstable environmental conditions; thus rose the plan to complete altar decorations with mosaics and transfer existing paintings into mosaics.

It was in the Fabbrica di San Pietro's laboratory where research was successfully conducted to improve enamel glass, creating a much more vast array of chromatic shades. The Vatican mosaicists would now have in excess of 15,000 color samples at their disposal. The lab's invention of opaque glass proved critical for the completion of transforming from canvas to mosaic all the works of the Vatican basilica. The mastery of their work enabled the creation of such marvelous mosaic transpositions from extremely complex works of art, as seen in Rafaello's Transfigurazione, considered as the most beautiful painting in the world.

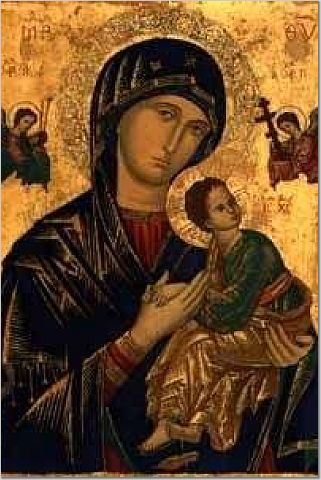

Framed within a great arch of gorgeous marble, the whole constitutes an effect so radiantly beautiful that one might well imagine it to be a sunlit vision of another and better world.This masterpiece is on the southeast wall of the dome (number 14 on the plan of St. Peter's), opposite the statue of St. Peter.

The mosaic copy in the Basilica

Cool, no?

![[Unam Sanctam]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiymQ2adTjpZ1ABhPBbBBquiPCxeQrc4Jy_97vOikT0wGQeJleriiXQy6ebnb0jrYe-TfvcK77txStB4aIwVAdD41ZdMkVfNtFGC0JX6LBV9B8mfeRZaIAM7Sj-011ag3DiKQzv/s1600/headerdivinemercy.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment